If I’m approached about a consulting opportunity I usually have people fill out a questionnaire to get a better feel for their situation. I’ve been doing this for 2 years and the answers provide a pretty panoramic view of the issues people face when embarking on these sorts of endeavors.

To better illustrate how people need to make decisions in these circumstances it’d behoove us to take a look at the aggregated answers to see where people’s assumptions might be off.

The results are very revealing. It turns out there are 3-5 issues that people regularly deal with, and without any prior knowledge of how to deal with them it’s easy to paint yourself into a corner. But without a little bit of foresight can help you sidestep divets in the ground.

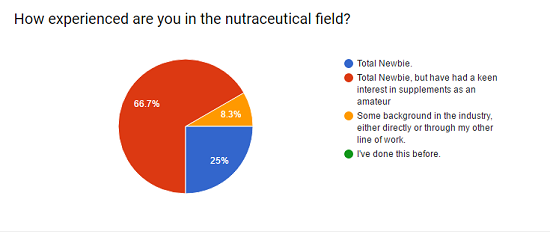

Question 1: How Experienced Are You in the Nutraceutical Field?

According to the results most of you start a little wet behind the ears, and no one’s walking into this with a lot of tangible experience.

Is industry knowledge a pre-requisite for success or is it easy to pick up on the fly?

In my opinion it’s not too important if you can figure out how to get the product made.

From what I’ve seen you don’t need a lot of prior knowledge about the nutraceutical industry if you’re very good at marketing. I’ve met about a half-dozen people who make a lot more money than me as business owners despite knowing much less about the industry and the one thing they all have in common is that they’re intense marketers.

They go about it in different ways, but they all have an ace in their pocket that allows them to continually bring in new customers. And they’re not shy about milking it for whatever they can. In person they’ve never struck me as being particularly intellectual or concerned with the world at large, but they have a distinct type of intelligence that’s hard to classify. It’s like an expert carpenter who’s figured out how to size up a job and understands exactly where to strike his hammer to get the biggest impact for his work.

They can’t necessarily explain why it works, or care to understand the process too much, but nonetheless have an astute sense of how to aggressively go about getting customers. To many people their approach might come off as distasteful, but that’s mostly because they don’t seem to care much about the social desirability of what they do as long as it works. None of them have struck me as being the least bit idealistic.

The ability to have a narrow-minded focus on making money and a willingness to bluntly do whatever it takes to achieve that is a unique skill unto itself that not many people have.

I’m not sure if this is coincidence or not, but none of them have used social media as their primary way of getting customers.

If you don’t know what you’re doing the big hurdle is figuring out how to get your product manufactured in a way that’s congruent with your marketing claims and budget. For many people this means discovering your business idea is no longer valid because your product can’t be made to your specifications on your budget, which forces you to erode your marketing claims to the point where they’re no different from anyone else, removing your reason for getting started in the first place.

When it comes to product ideals most people fall into two camps: they have a pristine vision that’s unique and incredibly expensive to make, or no standards at all so long as they think they can make a buck.

Both approaches have their problems. Pristine products with lots of certifications are great, but that usually means high order minimums that overwhelm your capacity to sell. It’s best to have your order quantity and sales quantity be in harmony and for most people that means starting as small as possible. But sourcing unique ingredients isn’t like shopping at Wal-Mart and you can’t just add the amount you’d like into your grocery cart before checking out.

It’s not unusual for differentiating ingredients to push your order minimums up several thousand bottles and that usually presents first-timers with a conundrum: do you go all-in to give your product the best chance to succeed or do you diminish it and risk that it won’t be worth selling at all?

This is a very prescient question and the best answer depends on your stance on a survey question that’ll be covered later in this essay.

Making products that are cheap but have high markups is a viable strategy but you have to get certain details right. Mainly, you can’t sell to people that will be able to tell that you make cheap products. This means you can’t target the infovorous hyper-sharing folks that are so commonly the entry point into a market for new brands.

Instead you have to migrate to where low-information people consume their information, which is usually broad-based mediums that finance themselves with paid advertising. Radio, TV, telemarketing, etc. Here you run into a similar dilemma as product purists but with a different face: advertising budgets that usually require a lot of money if they’re going to have any shot at working.

So while the product purist has to decide if they want to go all-in and buy the characteristics that will make their product unique, the marketing maven has to decide if it’s going to be worth it to commit to the marketing channels he needs in order to reach the people that’ll buy his product.

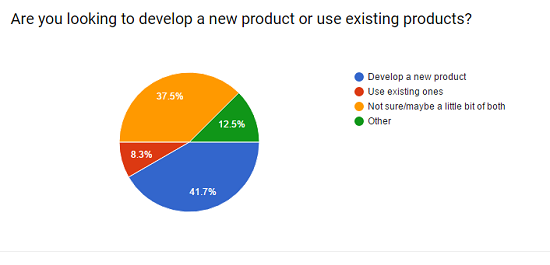

Question 2: Are You Looking to Develop A New Product or Use Existing Products?

The viability of creating your own product or selling someone else’ largely depends on your business model, which I covered in more detail in my article on private labeling.

If you’re looking to bring a new product to market you should swallow the knot in your stomach and make a custom product because that’s the only way you’ll have the differentiation and margin needed to blaze new trails.

Private labeling is suitable if your product line is not the main point of your business and you have some other customer acquisition channel you can add your private labeled products on top of. Medical professionals, health stores, and people who already have an online presence are good fits.

Most companies can’t afford to go through all the work of blazing new business trails only to sell someone else’s product when they get to the end of it. There’s not enough margin. You could potentially do private label-to-custom but you’ll have problems with market penetration that will make it harder for you to differentiate enough to finally get to a large order.

The majority of private labelers are best suited for small orders of a few dozen bottles at a time for non-supplement companies that want to add extra profit channels.

It’s okay to not be that kind of company as long as one of the following conditions are met:

- You’re using the private label product as a “fill in” to compliment the stronger custom-made products in your supplement line. Ie, some people would like it if you sold vitamin D even though it’s not your main product and it makes more sense to do a smaller private label than a large custom run for a commodity product.

- At large orders the private labeler gives you significant discounts over the standard 40% retailer markup. This way you can approach the unit pricing of the custom product and still have the benefit of them handling the details of the manufacturing.

- You are particularly good at marketing and can sell enough of a private label product to justify a custom order.

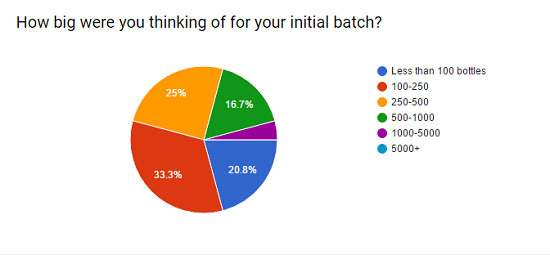

Question 3: How Big Were You Thinking of For Your Initial Batch?

Mmm hmmm……….

People are all over the map here, and not in a good way. One of the details that’s hard to understand for industry newcomers is what the world looks like to a manufacturer.

Even now, I’m still just understanding it, and it’s difficult to wrap my head around. When it comes to perspectives you’d be hard pressed to find two parties who approach the world as differently as a supplement manufacturer and the typical person filling out my questionnaire.

Most people looking to enter the industry are doing so with their personal savings, which is usually around $10,000-$20,000. Most manufacturers preside over a 100,000+ square foot facility that required millions of dollars in CapEx to build. They have large fixed costs which puts a pretty stiff floor on what they can afford to do and still make money.

Most manufacturers make most of their money from a few very large customers. When the right MLM company or drugstore comes along they’ll make 100,000 kilos at a time of something.

There’s more work involved in making 100,000 kilos of something than 500, but it’s not proportionally larger. The amount of testing, machine maintenance, and R&D is roughly the same, and even the time it takes isn’t that much larger because they can just use bigger machines.

Anything less than 1,000 bottles amounts to pixie dust to your typical manufacturer.

For most people starting out, the amount of money they’re using represents years of saved labor to get to that point, so everything they do seems incredibly important. Anything they need that costs more than they can afford feels extractive.

Manufacturers start from the completely opposite viewpoint. Runs of 50,000-100,000 bottles feel right, and by the time they get to less than 5,000 they feel like they’re doing you the favor. They also put a lot of thought into attracting the right customer, which usually isn’t the person who’s starting out and wants 500 bottles made.

The newbie with a $5,000 budget and 500 bottle test run usually ends up coming off like this:

If you’re just starting out you don’t want to be Bill Murray in that video. It’s easy to become him if you’re not careful.

If you have modest finances to begin your venture you’re already starting off with some headwinds and you need to make sure you understand the landscape to give yourself some extra oxygen to placate your lack of cash.

A good first step to overcome this ignorance would be my article on how to deal with manufacturers.

A second would be a consistent recognition of how your situation probably appeals to others and act accordingly. You should also anticipate starting with at least 1,000 bottles if your product is at all unique.

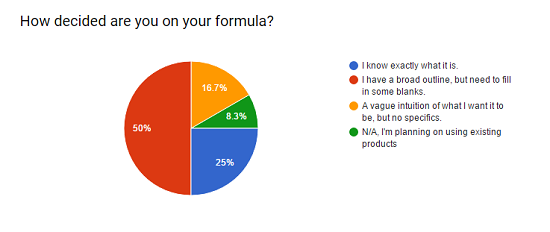

Question 4: How Decided Are You on Your Formula?

The big obstacle in formula development is turning your wish list into a to-do list. Most people start looking for manufacturers with lofty ambitions because they think they’ve targeted a big hole in the market that’ll get them penetration.

Most people have to backtrack from their original version for one of the following reasons:

- The ingredient doesn’t actually exist. This is often true when people want a nutrient that’s certified organic. Most isolated nutrients (like CoQ10 for example) are either made synthetically or extracted from a plant, often using a solvent that prohibits the ingredient from being certified. For example, there is no organic lutein, because in order to extract it from the marigold flower you have to use hexane or methanol, neither of which is approved by the organic standard. So lots of people have a formula that’s plum filled with all these trend-setting organic ingredients which can’t actually be bought.

- The ingredient is only sold by one or a handful of suppliers. If an ingredient is developed with some remarkable (and sometimes unremarkable) technology that has a patent on it then chances are all yellow brick roads will lead to one seller, which usually means really high prices and minimums. This is true of methyl folate, plant DHA, vegan vitamin D, and whole food vitamins, among others. In general there is an arms race to develop new ingredients with unique certifications because that’s where the money is these days. Overall sales of supplements are flat but there’s hot demand for getting the same ingredients from better, cleaner sources. So there’s a big rush to be the first company to adequately veganize, organify, or plant-base something that hasn’t been done so before. And then they get a patent. And then you have to pay 10x more if you want to have it in your formula. If your formula is chock-full of patented ingredients you are almost definitely putting yourself down this road.

- The ingredient list is overwhelming. If you’re requesting 1,000 bottles of something be made and you want to sprinkle in 50 mg of 8 different things then you’re probably driving yourself to very high unit prices to compensate for the fact that you’ll be leaving the manufacturer with unused inventory.

All in all, it’s hard to develop a genuinely unique formula while being economical. For most people it’s usually best to have one that’s merely good but with a distinct benefit, and then cultivate the right sales channel for it in order to give yourself separation.

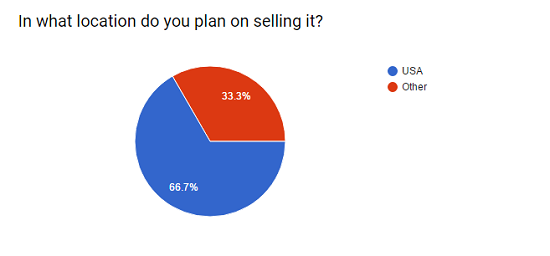

Question 5: Where Are You Planning on Selling Your Product?

The majority of people I speak with are from the USA, so most of these international ambitions mean people want to export.

My feelings on exporting are mixed.

On one hand, the world’s a big place and there are billions of people who are going through an industrial process that America has already completed, so it makes sense to do what it takes to expand your market. Lots of companies, including Nutraceuticals, experience most of their growth internationally.

On the other, new companies have thin margins and exports have high regulatory overhead. I frequently get the impression companies go into exports without the operational savvy to maintain it and this is sometimes more trouble than it’s worth.

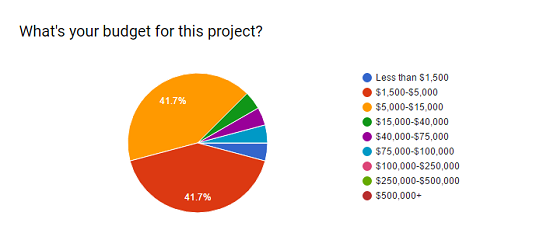

Question 6: How Much Money Do You Have to Get Started?

For the most part I don’t think nutraceuticals are a great business to get in if you have an ultra-thin budget. The product overhead is too high and the growth coefficient to the market is too low.

In investing parlance good supplement companies tend to be value stocks, not growth stocks. You can get consistent cashflows, but it’s hard to be a unicorn unless you have a lot of corporate backing.

If you’re reading this blog post in earnest interest then I can only assume that that doesn’t describe your situation.

As a rule of thumb $10,000 is a safe bet to get off the ground modestly. If you want to make a liquid it should be more like $25,000-$50,000.

Premium suppliers can easily increase your order minimums several thousand bottles. People who want to make a comprehensive product with lots of different certifications are likely to run into this problem.

It’s important to realize that your capital expenditures increase proportionally to your sales, so if you start fast and lean you’re going to have to stay that way as you grow, even if things are going really well. That means it can be hard to ever take money out of your business the first several years, and bootstrappers should take note accordingly.

If I were doing it over again, I wouldn’t go into the natural product business unless I either had a really unique ingredient that wasn’t being sold elsewhere and/or had at least $30,000 – $50,000 to get started, even though you could do it for less.

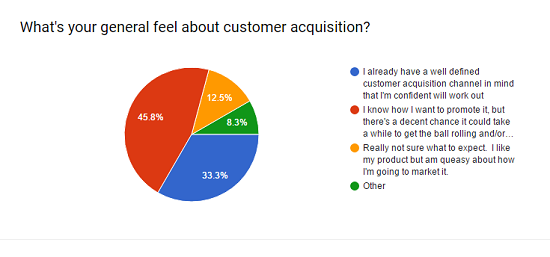

Question 7: What’s Your General Feel for Customer Acquisition?

Besides how good you make your actual product, getting your marketing right is the biggest determinant of your success.

There are a few supplement companies that get by today without being good at marketing, but they were started a long time ago. All the new companies are great at it, and this will be true for you too if you want to get over.

The most important part to effective marketing is making sure you know how to reach the people that make sense for your product. Your customer, marketing channels, and manufacturing specs all have to be in-sync if you want to get over.

For example, you could reasonably sell to both the elderly and vegans, but you’d have to align your business in very different ways to do either successfully.

Old people buy a lot of supplements. They have to buy a lot of supplements because the only thing they want to do is feel young again. If your product helps them feel young again, they won’t much care what’s in it, whether it’s certified organic, or any product benefit you could spend money on.

If their back feels better when they wake up in the morning then it works. Period.

That sounds like the ideal customer, but with one caveat: they’re expensive to reach. For the most part they don’t form a lot of their buying decisions through social media, and tend to consume their information through channels that have economies of scale: print, tv, etc.

Vegans are almost the exact opposite: young, infovorous, well-connected, but extremely demanding. So if you hit the right high notes your product can sell itself, but you’ll likely have to front a lot of risk in order to make it appealing to them.

Creating the right marketing channel is entirely about finding the right niche. It’s a lot like creating the right menu for customers at a restaurant. Almost any style of food could conceivably work, but you’ll have little hope if you don’t offer the right sort of food to the people who walk in your door.

Both greasy diners and high end brasserie’s can achieve great success, but one would never meet success by trying to think it could be like the other.

You should think of your natural products company the same way and mold your business appropriately. And the time to galvanize your customer base is before, not after your product is released.